Developing appropriate ankle mobility, especially dorsiflexion, where it has been lost is incredibly important for athletes across all sports.

Introduction

I received a question on Twitter the other day that I was unable to answer in 280 characters (or even a thread) because the process involved is complicated to explain even though it’s relatively simple.

Developing ankle mobility takes time and focus but it shouldn’t take 4 years to achieve. In this article, I’m going to show you the elements that go towards improving your ankle mobility.

What’s more, the principles apply equally to any joint where you have restriction that doesn’t spring from an injury.

Before I start, I need to stress that these are general principles that make an enormous difference to most people. Because I don’t know you or your particular case, if you have any concerns, a visit to a good physiotherapist (physical therapist) would be a good move.

That said, there is a lot you can do, and I believe that everyone should be able to do most of their own body maintenance.

What is Mobility?

First up, I need to clarify what I mean when I talk about mobility. I’m very careful to call it that because it differentiates mobility from flexibility.

The simple explanation of flexibility is that it’s the length that a muscle can attain when you move its origin as far away from its insertion as possible. Many flexibility programmes are very good at helping you to attain long muscles but make little, if any difference to useful mobility.

In fact, an orthopaedic surgeon once told me that, under anaesthetic, he would easily be able to put my knee on my forehead! We’d been discussing my inability to touch my toes and my excessive flexibility routine to get there.

If he was right, then my (and your) muscles have all the flexibility they need.

Mobility, on the other hand, is mediated by your nervous system. I like to think of it as the amount of the range of movement around a joint that you can control under load.

Your nervous system will not allow you to go beyond that controllable range under load because it has your survival as its primary responsibility: risking a dislocated joint isn’t a good idea if you have to run after your food or run away from lions.

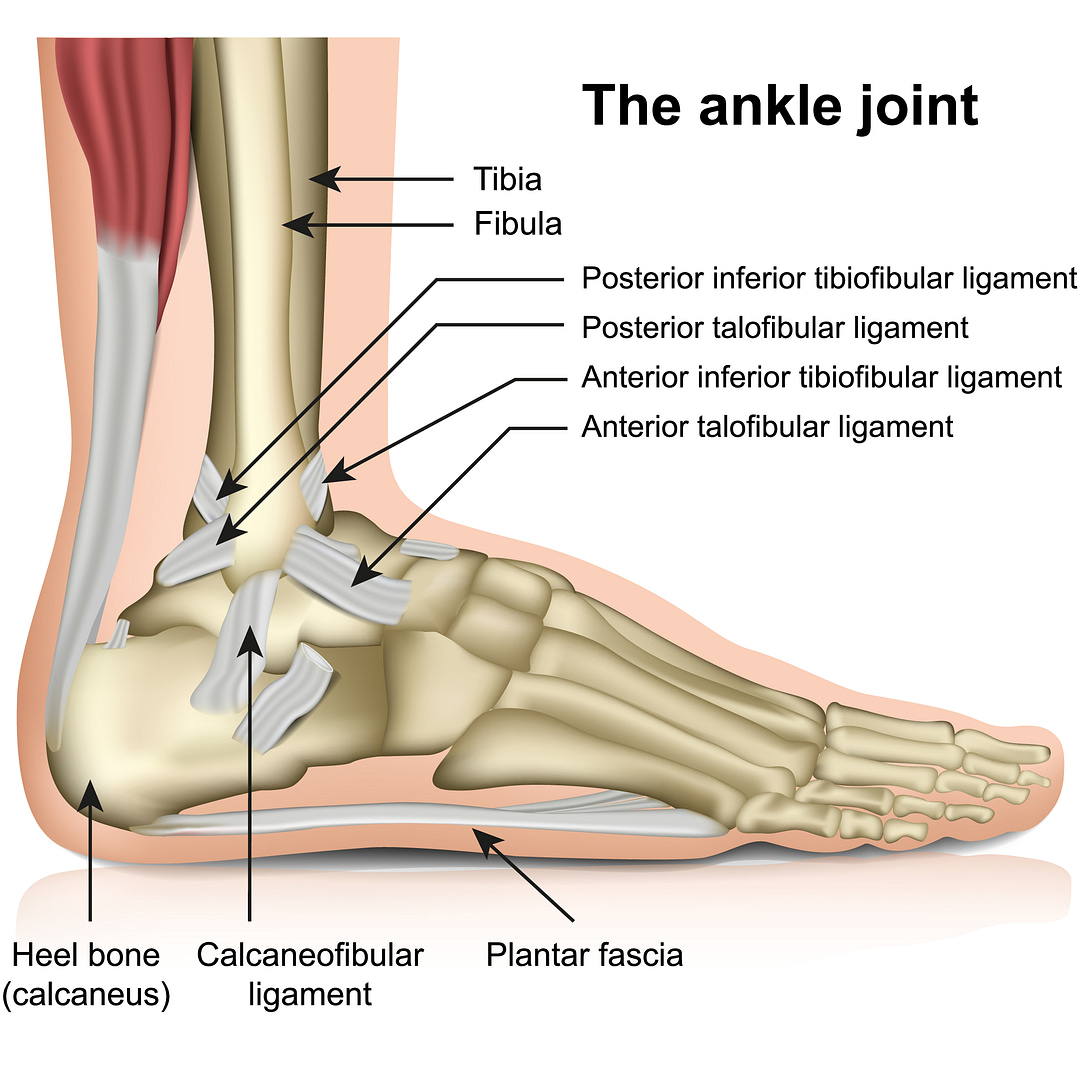

How Does the Ankle Move?

Simply put, your ankle moves in 4 directions…

- Plantarflexion - point your toes

- Dorsiflexion - pull your toes up towards your knee

- Inversion - rolling onto the outside of your foot

- Eversion - rolling onto the inside of your foot

Although all movements can be restricted, the ones where most people notice restrictions are plantarflexion and dorsiflexion. Dorsiflexion is the position that we'll focus on most in this article because the Twitter question was about achieving the bottom position of a squat. I plan to update this article in the near future to include, at least, plantarflexion.

Why Does Developing Ankle Mobility Matter?

The first and most important reason that you should work on developing ankle mobility is that stiffness in the ankle is going to have a knock-on effect further up your kinetic chain. The worst case is that it causes you pain, for instance in your lower back, as your body tries to find the mobility elsewhere that you should have at the ankle.

Secondly, a lack of ankle mobility compromises your ability to perform movements in sport and other physical activities properly.

Examples

- You’ll find that swimmers have great plantarflexion and inversion, whilst triathletes don’t. The “toes down” kicking position I see in triathletes in the pool are often due to mobility restrictions rather than simply weak calf muscles.

- Restrictions in dorsiflexion will affect your ability to hit rock bottom in a squat with your heels on the floor. These are most often due to muscle tightness or joint position.

What Affects Ankle Mobility

The most obvious thing that will affect ankle mobility is any kind of orthopaedic injury repair, the most common being the use of screws and plates to repair a broken ankle.

If that’s you, you will always have a compromised range of motion at the ankle, although you could almost certainly improve it.

If you don’t have orthopaedic repairs that limit joint range, you can also have poor ankle mobility because of tight musculature, muscular weakness, poor joint position and knock-on effects from elsewhere in the body.

Calf Flexibility

There are two major muscles in your calf that can become tight, limiting your ankle mobility.

The big “movement muscle” in your calf is your gastrocnemius. This usually gets tight because it’s tired or injured. Unless that injury is chronic (long-term), Gastrocnemius doesn’t usually appear to be the real culprit.

The Soleus muscle is a postural muscle and it’s this that seems to be problem in most people’s lack of ankle mobility. It becomes chronically tight, usually because it’s doing the work of muscles elsewhere in the kinetic chain and then, out of habit, stays tight.

Anterior Tibialis Strength

Not only do your calf muscles have to be flexible enough to allow your ankle to dorsiflex, your tibialis anterior - the big muscle on the front of your shin - also needs to be strong enough to pull the toes up into dorsiflexion.

The calf muscles do so much in most athletes that they become very strong and dominate the Tibialis Anterior.

As an aside, the shin splint symptoms many runners experience aren’t because their shoes have worn out or their mileage is too high, they’re due to this imbalance between calf muscles and Tibilalis Anterior.

Joint Position

You don’t need to have had a surgeon put plates and screws in your ankles for your ankle joint to be in a poor position.

Sometimes, just due to habitual stuff we do in our everyday lives, joints move slightly out of alignment. While this might not be painful in the range of movement that we normally use, once we start challenging the edges of that range, we find that we have restrictions and even pain.

Unstable Knees

Lack of ankle mobility can have nothing to do with your ankle at all.

Unstable knees are just one example that force your body to try to find stability elsewhere and that can manifest as a lack of mobility in the joints that compensate; it could quite easily be the ankles.Steps to Improve Ankle Mobility

There is overlap between all the items mentioned in this section.

Some interventions might be the thing that makes a difference to you, all on their own. Others might work better in combination and still others might not work for you at all.

As with any interventions, you must test them, learn which ones work through observation and then use those that work for you.

Understand Normal Range and Test it

Before you start, you need to test the mobility you already have.

Professionals can measure joint angles using goniometers, but this isn’t practical or even necessary for you at home.

A normal range can be established by adopting a lunge position with your toes 10cm from a wall and touching that knee to the wall while the heel of that foot remains on the floor.

If you can do that, you have normal dorsiflexion range. If you can’t you have work to do.

Now that you know how much range you have, it’s time to work on improving it.

A physiotherapist can also measure passive range of motion at the joint but, in the absence of pain, it's loaded range that matters.

Improve Tissue Quality

This is where we start. If your tissues don’t move freely, gaining flexibility and mobility is difficult to do.

It's common for tissues that are meant to glide smoothly over each other to become sticky so that they no longer move freely. It's also possible for muscles to develop tight bands in the muscle tissue, often referred to as trigger points.

You want to do tissue quality work on Gastrocnemius, Soleus, Tibialis Anterior and Plantar Fascia.

The easiest way to make a difference here is to use a foam roller or massage stick on your calf muscles and tibialis anterior, and a lacrosse ball or similar on your Plantar Fasciae. You’re looking to find sore spots and maintain pressure on them until the tension causing that soreness dissipates.

Two to three minutes per leg is enough in any one session. If you do too much at a time, all you do is wake up sore the next day.

You can also use a lacrosse ball (or similar) to apply extra pressure on particular sore spots.

What you’re doing here is similar to what a massage therapist or physio will do when working on trigger points. The difference is you can do this daily, while most of us can’t see a massage therapist every day.

Start by rolling up and down the length of the calf, looking for sore spots in the muscle belly.

Using the roller, pin the tight (sore) spot in the calf in position using the weight of the other leg/foot. Then move the foot into and out of dorsiflexion (pull the toes up towards the knee and then point the toes).

You can do something similar to what you do with the roller, using a lacrosse ball or massage stick.

Use the same principle to work on Tibilalis Anterior, although you’ll be using your bodyweight to pin the muscle in place.

Using a lacrosse ball, start by rolling the length of the underside of the foot and then roll across the fibres, starting at the front of the foot and working to just ahead of the heel.

Improve Flexibility

Once you have improved your tissue quality a little bit, some stretching is in order. You want to hit, as a minimum…

Gastrocnemius - this is the standard runner stretch where they look like they're trying to push the wall over. To stretch the Gastroc effectively, the back leg needs to be straight.

Soleus - the same as the Gastroc stretch but with the back leg bent. You'll feel the stretch lower in the calf muscle.

Tibialis Anterior - It's unusual for the problem to be a tight Anterior Tibilalis.To stretch it, though, simply sit with your feet together and under you. Increase the stretch by raising the knees off the ground a few inches.

Plantar Fascia - take the foot into a dorsiflexed position and add stretch by pulling the big toe up towards the knee with your hand. Alternatively, assume a box position on all fours and rock back so that your toes take your weight in a stretched position.

All stretches should be held for between 30 seconds and 2 minutes. This is a bit of trial and error; figure out how much you need in order to make a change.

Correct Joint Position

Sometimes, the tibia and talus bones in your ankle joint may not be in a good position to articulate properly. Using an exercise band to apply gentle traction in one direction or another can help to reset the joint position.

To manipulate the position of your tibia, place the band above the ankle joint, get good tension on the band and then find a way to get that ankle into the position it would be in at the bottom of a squat and “noodle” around looking for the limits of your mobility.

For some people, this will simply be sitting in a deep squat or using a prying goblet squat. For others, that might mean using a modified lunge/split squat position. As long as you don’t hurt yourself, how you get there is up to you. You may initially need to put a block under your foot to elevate your ankle if your mobility is very compromised.

You can also manipulate the tibia position in more of a plantarflexed ankle position by adopting the top of a split squat position with the band in a similar position. Or move between the top and bottom positions of the split squat.

Another joint position issue can relate to the position of the Talus bone. You can reposition the talus by using the band to apply traction in a backwards and down direction with the band positioned in the angle between the foot and leg.

Again, move into and out of ankle dorsiflexion by moving the knee in front of the toe with tension on the joint.

It’s also possible to reposition the talus by holding the inside of the joint (where the band would have been) between thumb and forefinger and moving the joint into and out of dorsiflexion against that resistance.

I figured this manipulation out one day when I felt impingement in one of my ankles and went after making it feel better by manipulating the joint. It worked and I proudly told my physio friend about my discovery the next morning. “That’s exactly what I would have done if you’d come to see me.” she said. Sometimes, just trying to work out the solution to the problem by experimentation is the magic pill.

Correcting joint positioning is usually more effective under load but if you have any pain on weight-bearing, this is a good option.

Test Again

Any time you try an intervention to gain mobility, you MUST retest your range of movement afterwards. If it improves, you know you’ve found something valuable. If not, you’ve learned something that doesn’t work for you and a different approach is needed.

Learn Good Positions Under Load

When we’re talking about dorsiflexion, one of the more extreme expressions of ankle mobility in that movement is the bottom position of the squat.

I believe that the best way to learn that position is the prying goblet squat.

You don’t have to descend into the bottom position, just start down there and move around to find the correct position. Spend time in this position with very little load and learn what a good position feels like.

What’s great with the goblet squat is that the kettlebell, dumbbell or whatever you use acts as a counterweight so that you can find a good deep squat position without falling over or fighting to hold the position.

If you can’t achieve that position yet, use blocks under your heels to reduce the range of movement needed. Alternatively, use a box or bench to limit the depth of the squat and slowly reduce the size of the box.

Understand the Knock-On Effects From Elsewhere

This is huge: it is possible, if not probable, that your lack of ankle mobility is a compensation reaction to lack of stability somewhere else in your kinetic chain.

I’ve mentioned this elsewhere in this article, but it bears repeating. Often, it’s the joint directly above (your knee) or the joint below (your foot - yes, it’s a series of joints). That’s not always the case. It could be instability anywhere that you compensate for in your ankle.

Everyone has their own compensation patterns in the search for stability and mobility.

Personal example: The damage caused by my hernia surgery means I habitually try to find stability for some movements by tightening my jaw.

Summary

Like everything else to do with mobility, developing good ankle mobility is actually a fairly simple process, once you know what to do, but takes a fair bit of patience if you have significant restrictions.

To summarise the process:

- Test your range of movement

- Work on tissue quality

- Work on flexibility

- Work on joint position

- Test again

- Once you have a good range of movement around the joint, lightly load that position and learn what good positioning feels like.

That said, you should see some change from the very first session of working on it. If you don't, you are almost certainly working with a mobility or stability restriction elsewhere. Stick with the ankle for a few sessions before consulting someone who might be able to help you figure out where in your kinetic chain the issue might be.