Low carb workout nutrition is a much-debated subject. Can you even train or compete effectively without eating carbohydrate foods?

In the almost 7 years that I have eaten a low carb diet, I’ve studied and tested a bunch of different approaches to low carb workout nutrition for me as an athlete and for those I coach, who choose to train and compete as low carb athletes.

I’m very aware that athletes are almost always ahead of research and this is becoming the case even more as we discover ways to improve health and performance that do not have significant profit-potential for sports nutrition companies.

It’s difficult to sell sugar-laden, highly processed non-foods to someone who commits to eating real food to fuel their training.

Yes, there are those making and selling synthetic ketones, but there are a few issues with these too.

- Up to now, they’ve been fairly expensive.

- Seeing as your body can make them, why would you spend the money?

They aren’t real food. So, once again, if you’re committed to fuelling your efforts using primarily real food, these become problematic.

One reason advanced for using these is that they claim to allow you to keep eating carbs but still get the benefits of ketosis. I’ve seen reports of athletes suffering similar effects to the “sugar bonk” when using synthetic ketones, so this might not be as effective as hoped.

While I am a low carb athlete and encourage you (and the athletes I coach) to give low carb workout nutrition a fair trial, I am not completely anti the use of carbohydrate food in the right place to enhance competition, training and recovery.

What I am, is very clear that carbohydrate foods are not required to be consumed in order for you to remain healthy. They are also not necessary for high performance in your sport except, perhaps, if you’re at the very pointy, elite end of the field.There are a few really good reasons for limiting carbohydrates, using low carb workout nutrition approaches during training and even during competition.

The advice, starting in the 1980’s, promoted in books like The Lore of Running by Tim Noakes and still promoted today by the likes of Nancy Clark and Louise Burke, is that we need carbohydrates in order to perform during exercise.

Tim has since changed his mind on this and symbolically tore the pages out of his book.

This advice has led to many elite athletes developing Type 2 Diabetes (T2DM) after retirement or even late in their athletic careers. Stand-out examples of this are Sir Steve Redgrave (5 Olympic Rowing Gold Medals), Bruce Fordyce (9-times Comrades Marathon winner) and Oscar Chalupsky (12-times World Surfski Chamion).

In fact, even Tim Noakes, a huge proponent of carb-fuelling for athletes and the co-inventor of the first energy gel (the SRN Squeezy, of which I consumed many in my early triathlon days), developed T2DM.

The good news is that by embracing a low carb nutrition approach, Bruce, Oscar and Tim have all reversed their T2DM.

The deterioration that these athletes saw in their health and performance is seen throughout the world of the amateur athlete. The metabolic damage caused by the body constantly having to deal with the assault of sugar works against the reason most people start exercising in the first place: it destroys your health.

I was once chastised by the wife of a sports nutrition company owner for suggesting that the reason so many amateur athletes were overweight despite training so hard was her husband’s products. As you can imagine, my comment didn’t go down well. I stand by it: sports nutrition companies are slowly poisoning the people who consume their products and dooming many of them to metabolic disease.

A low carb workout nutrition approach resolves these issues for most people and reinstates the positive benefits of exercise.

Especially for amateur athletes and folks who train recreationally, low carb workout nutrition can have several positive benefits on performance.

People who use low carb nutrition tend to have an easier time controlling their bodyweight and their body fat levels. I’ve written elsewhere about why this is important but it’s enough to note here that control of body composition helps across both power and endurance sports.

- Cyclists and triathletes obsess about power to weight ratio.

- Lighter runners run faster.

- Wrestlers, MMA fighters and powerlifters often have to make a weight to compete.

- Bodybuilders often do bulking and cutting cycles to gain muscle and drop fat.

Athletes using low carb nutrition experience less soreness and better recovery from sessions. It’s been suggested that this is because Beta-hydroxybutyrate, one of the ketone bodies produced and used as a fuel from fat metabolism is anti-inflammatory.

It’s also likely that fat metabolism simply does less damage to the body than does the oxidation of glucose, requiring less recovery from that damage.

A lot of athletes - I’d suggest most athletes - experience digestive distress during longer events like Ironman and ultra-marathons. They get this from following the advice to consume as many calories in the form of carbs as possible during their event. Many a race has been ruined by periodic stops at portable toilets. By adopting low carb workout nutrition, you’re able to reduce carbohydrate intake to a minimum during races or even eliminate it altogether.

Athletes using a low carb nutrition approach also report more level energy and better mental clarity. Mental clarity is a huge advantage in any sport because tactics and decision-making are, more often than not, the deciding factor between two athletes of equal physical ability.

The Australian Cricket team are reputed to have adopted low carb nutrition with improvements in both physical and mental performance. If there’s any sport where the ability to maintain focus and be mentally sharp over an extended period is an advantage, it’s cricket.

Two outstanding examples of successful elite athletes using low carb workout nutrition are Paula Newby-Fraser (8-time winner of Hawaii Ironman World Championship) and Zach Bitter (World 100 mile and 12-hour Record Holder, both records set on a running track).

It would be tempting to say that nobody should use carbohydrates as part of their athletic nutrition strategy, but this ignores some potential benefits for some people.

We’re all slightly different and what works for me might not work for you.

So, while stressing that exogenous carbohydrate intake is not essential for health or performance, here are two benefits that I’ve observed and which a lot of people report.

Have you ever been told by “bro science” at the gym that you have to have carbs to be able to get a good workout? What they should say is “I have to have carbs to get a good workout.”

They’re convinced that carbs are somehow needed in order to lift well because the intensity of the exercise uses carbs.

That is true to a point. However, you have enough glycogen stored in your muscle tissue to fuel ~90 minutes of continuous fairly high intensity exercise (cyclists would call this exercise at Functional Threshold).

The vast majority of people in the gym will not deplete this. They’ll feel like they’ve depleted it if they are lifting to failure, but what they’re experiencing is probably fatigue of the muscles they’re working, resulting in an inability to contract as hard.

So, why do the carbs help?

It’s almost certainly a mental effect that they’re experiencing, a bit like the placebo effect. If there’s a fuel effect, it’s almost certainly at the level of replacing liver glycogen and maintaining glucose supply to the brain which, in someone who is not fat-adapted, requires glucose to operate effectively.

There have been some studies performed that showed a beneficial effect of swilling a sugar drink around in the mouth and then spitting it out. Clearly, this benefit is not from extra energy intake, but is a nervous system (brain) effect.

This is where the arguments rage.

If you are an amateur athlete, there is a good chance that this doesn’t apply to you because, if you’re fat-adapted, your system can deliver all he energy you need to compete at a fairly high level for the duration of even the longest events.

On the other hand, if you’re an elite athlete or you’re racing at the front of the age-group field, including some carbohydrates as part of your workout nutrition might make a pretty big difference.

Contrary to what some will tell you, there is a limit to how much fat you can use for fuel per minute. That limit is below what you’d need to fuel the output which you’d need to win a professional Ironman triathlon, cycle race or marathon.

Whilst the best fat-adapted athletes can find about 14kcal/minute from fat, my rough calculation based on a world record marathon would suggest they’d need more like 20 or 21kcal/minute. Some of that will come from muscle glycogen and for a 2-hour marathon runner, it’s most of it.

[I have to stress, this is a rough calculation, not based on 100% verified figures, not based on testing and which makes a bunch of assumptions for simplicity, e.g. that they’re running at FATMAX, which they’re almost certainly exceeding.]

If, however, you have to go longer at a world-class race intensity (e.g. for Ironman), you’ll need to consume some glucose to be able to maintain your energy output for that period or you’d need to slow down a bit, which is not good for winning.

The good news is, that intake requirement is nothing like what is needed by the sugar-dependent athlete who can only find 7 or 8kcal per minute at FATMAX, access to which which falls off a cliff as soon as they exceed that intensity. Fat-adapted athletes have been shown to achieve FATMAX (the point where maximum fat is used) at higher intensity levels than carb-fuelled athletes.

If you have to perform multiple sessions in a day and these are anything other than fairly short, easy/steady sessions, eating carbohydrates during the first session and in the post exercise meal might help to replenish glycogen faster. This is the theory anyway.

The problem with glycogen replenishment is that it’s a trickle, whilst its usage can often be more of a flood.

Because of this slow replacement and the fact that at least one study showed glycogen replenishment to be at the same rate in both low and high carb athletes, it might actually make more sense to forego carbs in and after the first session, consuming them during the second session for direct use.

I know of a number of athletes who use the first approach with a lot of success. The second is something I’m trying for myself, based solely on my logical assessment of the implications of glycogen resynthesis being slow.

To read the mainstream sports literature, you might believe that low carb workout nutrition is impossible because you need carbs to be able to exercise.

The distinction that is never made is one of where and when carbs might be required, as well as where and when it’s unnecessary. This isn’t something on which you can make a blanket recommendation, and nobody should accept such a recommendation without thought, research and experimentation.

By itself, training volume doesn’t necessarily require any consideration of carbohydrate intake, either during or after the session.

I’ve known athletes to do 8 hours or more of cycling without anything more than water and salt.

Intensity is what makes the most difference.

Beyond an hour-and-a-half or so, above a certain intensity level, some sort of carb intake might be helpful. Simply speaking, if the intensity of your session is any higher than your FAT MAX, you will be depleting glycogen and sessions over 90 minutes could benefit from a small trickle of glucose.

Density refers to how close together your sessions are.

Anything over 24 hours between sessions and you’ll almost certainly not need any exogenous carbs to keep your glycogen stores full.

If you’re packing in multiple sessions per day, you’re probably still not going to make a lot of difference to your glycogen stores, but a small amount of in-session carbs in second or third sessions on the same day might make a difference to how good your sessions are.

Extra carb intake is probably a waste of time if later sessions are low intensity.Different types of training will have different glycolytic effects. Much of the information you find on this stuff is biased towards the “you need carbs” side of the argument, so it’s hard to figure out, but what follows is my very simplified explanation of those glucose needs based on basic energy systems.

Heavy strength and hypertrophy training will have a requirement for glucose to fuel powerful muscle contractions.

You’d have to spend a long time in the gym to completely exhaust your muscle glycogen because the actual time under tension in an average session is simply not going to be long enough to do so. The exhaustion that people experience is almost certainly due to contractile fatigue, not a lack of fuel.

Almost all cardiovascular training, including HIIT, can be considered aerobic conditioning because the aerobic system has to play a large part in any exercise over about 30 seconds for most people, perhaps a minute in an outstanding elite athlete (consider that elite 400m runners are spent inside 50s).

If you want to deplete your glycogen stores, you’d need a workout of about 90 minutes at your functional threshold intensity, which is pretty hard going. In fact, most people will fatigue, again from the inability of muscles to continue contracting hard, long before they deplete their glycogen.

Glycogen should be sufficient to cover the glucose needs of most aerobic conditioning workouts because high intensity workouts should be rare in a well-planned programme.

As an aside; this is another reason why grey zone training is not a good idea. It’s often hard enough to deplete glycogen more than necessary without actually building significant extra aerobic capacity.

I wanted to call this something other than Crossfit because they’re not the only people who mix strength and aerobic conditioning into a single workout. Once again, glycogen stores should be enough to fuel these workouts

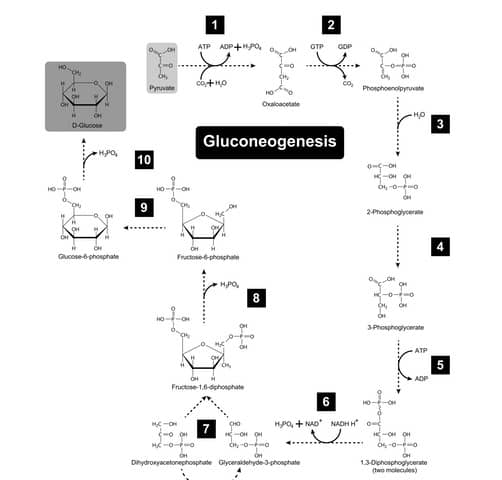

I’ve mentioned gluconeogenesis on numerous occasions, in my articles and across my social media. It’s the process by which your body makes glucose, either from protein or the leftovers - glycerol backbones - from fat metabolism.

For this reason, there is no such thing as an essential carbohydrate. The term “essential” refers to any nutrient that the body cannot make itself.

Essential nutrients include certain amino acids, certain fatty acids (EPA & DHA), Vitamin B12, Vitamin A (in many people, who don't efficiently convert Retinol to Vitamin A) and a host of minerals. They do not include carbohydrates.

The diagram below shows this process. Like pretty much any bodily system, it’s complex but it works very well.

A small amount of glucose is needed for brain and red blood cell function and quite a bit more might be required to refill glycogen stores. Your body makes all of this glucose because it’s a survival imperative that it do so.

The FASTER study showed glycogen refill rates to be the same in carb-fuelled athletes who were given a carb drink after exercise as they were in fat-adapted athletes who received no carbs post-exercise.

What this means is that nobody needs to worry about glycogen resynthesis, your body will do it regardless.

If you then need this glucose to support intense exercise, your body will use its stored glycogen. As noted before, this makes the ingestion of glucose unnecessary except in certain high-performance situations.

Some experts feel that the maintenance of metabolic flexibility requires that you use occasional carbs in your training. I’m not convinced that this is necessary unless you’re looking for that really high level of performance.

Having said that, there are 3 approaches used by people in the ketogenic athlete community that can act as an example, even for slightly less extreme low carb workout nutrition.

This is very simple; you stick to your ketogenic diet regardless of what exercise you’re doing.

For the keto folks, this means keeping your carbs below about 20g per day, but the approach is no different for those on 50g or even a little higher.

In a targeted ketogenic diet, you use supplemental carbohydrates before, during or after your workout, allowing for the “can’t train without my pre-workout” crowd, those who are doing extended workouts and want something as a “pick me up” during their session and those who feel they want to try to ramp up post-exercise glycogen storage.

Important with this approach is not to overdo the amount of carbs. Remember, you’re looking for as much fat metabolisation as possible. The carbs are only there to provide any extra calories that you can’t access in fat. And to give you the mental effect.

The idea of the cyclical ketogenic diet is to live and train in a ketogenic state for 6 days of the week (or whatever extended period you prefer), followed by a day of eating high carb foods, in the manner of a cheat day, similar to bodybuilders.

It’s theorised that this approach maintains hormone levels, resetting leptin for example, and topping up your muscle glycogen.

I can see the hormonal argument and some people report that this approach makes them feel better when training hard on a ketogenic or low carb workout nutrition approach.

This approach works best if you do a whole-body workout just before pigging out on the carbs in which you work as hard as possible to exhaust your muscles.

I can certainly see how this would work to refill glycogen for someone who is not fat-adapted. Based on the FASTER Study data, it seems that a fat-adapted athlete probably doesn’t need this regular infusion of carbs to top up glycogen.

Summary

Low carb workout nutrition isn’t simply a case of “do it” or “don’t do it”. Like so much in the exercise and nutrition world, we each need to test approaches to see how well they work for us.

There are good reasons, both for avoiding carbs and for including them in your low carb workout nutrition.

For most people, the addition of carbohydrates to their workout nutrition is unnecessary once they’re fat-adapted. Their fuel demands are comfortably met by the combination of fat and glycogen.

However, those at the high-performance end of any competition, especially in endurance sport are likely to need a small infusion of exogenous glucose to support the energy needs of their performance. The good news is that they have no need to practise eating huge amounts of sugar and don’t have the same risk of digestive tract issues during competition that those who rely on carbs do.

As always: if something is working for you, you need to keep doing it. When it stops working, you should try different things in order to get the best result for you.