Everybody should do some form of strength training. The exact form it takes will vary, depending on your tastes, the space and equipment you have available, and your level of expertise and confidence.

At its most basic, strength training is picking up something heavy and putting it down again, ideally fairly gently to indicate that you have the control to be lifting that heavy item safely.

Let’s face it, that’s just part of life. We pick things up, we put things down, we move our bodies through space and we even do simple things like unscrewing the lids on jars. All of these require a level of strength and it’s both remarkable and disturbing that so many people don’t even have the strength to manage the activities of daily life!

A friend of mine is an A&E doctor (that’s an ER doctor for my US friends). In a number of conversations, he’s raised the fact that he’s been seeing a significantly increased number of older folks in recent years, not for heart conditions or pneumonia, but because they’ve fallen over.

His assessment is that many of these people are not vulnerable to the cardiac and upper respiratory complaints that traditionally take our aged relatives, in fact they’re in quite good health in that department.

Instead, they are suffering from such advanced levels of sarcopenia (muscle loss) that they simply weren’t able to hold themselves upright when they stumbled. So, they fell and hurt themselves badly enough to need a visit to A&E.

Another acquaintance is a trainer in the USA, who works primarily with older adults. He tells me that one of the leading causes of death and injury in his state is elderly people falling and being unable to get back up off the floor. Apparently, it’s not unusual in his early consultations with new clients for them to be in tears because of their fear of getting down onto the floor; they’re rightly scared that they will never be able to get up again. Thankfully, his programme is such that they very soon regain that ability.

If we’re to be in better shape at 70 than the average person is at 20, one area we cannot neglect is that of strength training.

Strength sports are a “thing” in their own right, and volumes have been written about how to train for strongman, powerlifting etc. It’s not my intention to add to that body of work with this article.

Instead, I wanted to write a guide about how people like us, dare I say “average folks” can get strong for life and how people who engage in sports other than strength sports can enhance their sporting experience by getting properly strong.

My focus here is very much on strength. It’s not on the recently popular pursuit of “body recomposition”, which is basically a rebadging of bodybuilding for the masses. Whilst you can certainly expect to see changes in your body as you get strong, in combination with a robust nutrition approach, this is simply a pleasant and often welcome side-effect.

The introduction to this article has already touched on this question, but a little more detail might be valuable. The benefits of strength training touch on most areas of our lives at any age.

A strong, healthy body is a worthy receptacle for a strong, healthy mind.

Physical capacity is the ability to do “stuff” throughout our lives. This could be the ability to spend all day lifting and shifting in the garden or simply being able to open a jar of pickles for the kids.

My grandfather died at 65, quite young especially by today’s standards. But my abiding memory of the man was his sheer physical capacity, the ability to work all day on his smallholding and on the surrounding farms, where he was the local handyman/builder.

If it needed lifting, he could lift it. If it needed moving from one place to another, he could move it. He never did formal strength training, but the daily physicality of his life was his strength training. To my knowledge, he was strong like this until a week or two before pancreatic cancer took him.

Most of us don’t have lives that are filled with daily physical tasks that serve to keep us strong anymore. Our daily lives are more likely to be lived behind a desk or the steering wheel of a car. If we’re to be as physically capable as my grandfather, we must consciously include strength training in our lives.

Life is an athletic event and a very chaotic one at that.

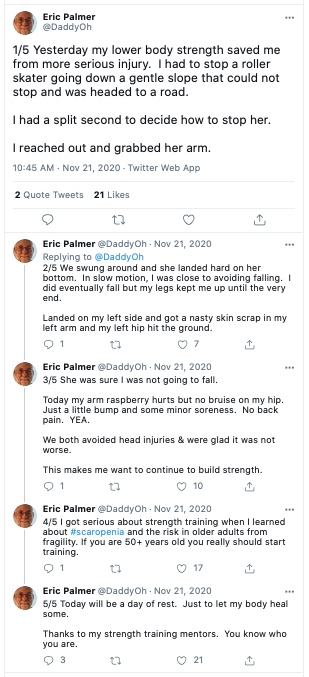

Rather than write a long paragraph about why strength training is important in this context, have a quick read of this tweet from Eric (@DaddyOh on Twitter), where he discovered first-hand just how powerful his strength training is for him.

The ability to respond to situations without getting seriously hurt, to stumble and not fall or to have a someone bump into you without leaving you sore for days is another worthwhile reason to get strong.

Western medicine has become extremely adept at keeping us alive. The average life expectancy in the UK is now roughly 81 years. Part of this is a dramatic reduction in infant mortality and another part is the ability of modern medicine to largely do away with fatal infectious diseases like smallpox and measles, which would have killed far more young people until the mid-1900’s.

Fortunately, or unfortunately - depending on your point of view - medicine has also become very good at keeping us alive beyond the point where we have any quality of life. We could blame our doctors and the pharma industry for this, but I believe that a large part of the problem lies with us.

Each of us has a choice as we begin to age. We either accept that ageing means an inevitable decline into frailty and a reliance on medication to keep us alive, or we do whatever we can to be healthy and strong into old age. Of course, there are no guarantees, but I certainly know that I’d like my future health to be in my hands as far as possible, not those of the pharmaceutical industry.

The term “healthspan” has been coined to differentiate the goal of the longest possible life, no matter the quality of that life, from the best possible quality of life for as long as possible. Ideally, we live long and healthy lives and drop dead unexpectedly.

Healthspan requires that we be strong, making strength training an absolute necessity.

With strength training comes an increase in and maintenance of muscle mass, with the advantage that more muscle provides more of a sink for the glucose resulting from any carbs we do eat or which our bodies synthesise through gluconeogenesis.

When you consider that some estimates put metabolic syndrome - the insulin resistant state that leads to Type 2 Diabetes (T2DM) and heart disease - prevalence in western populations at between 75 and 85%, as well as the T2DM epidemic currently being experienced in India, anything that can help with blood glucose and insulin control must be considered important.

This is the main reason many people, especially younger people, think of for starting strength training. The ability to be faster, stronger, and more durable becomes ever more enticing as you target athletic performance and feel that you have tapped out the benefits of the other training you’ve been doing.

Funnily enough, however, the sports performance benefit of strength training is often not due to an improvement in your ability to perform those sports specific movements, but in a reduction in injury risk from real life.

What we often overlook is the very limited range of movement and the very protected environment in which sport takes place. We become strong in the characteristics that are required for success in that sport and neglect other qualities, those which are necessary in our day-to-day lives.

It’s in these neglected areas that we’re vulnerable to injury. So, far from our sports being to blame for that sore knee or hip, it’s our ill-preparedness for life in general that’s responsible. Nevertheless, that injury will mean we have to take time away from training or competing to heal.

When you consider that the rule of thumb for endurance athletes returning after time off training is four weeks to regain the losses from one week off - this refers more to higher level fitness like speed endurance - you can see how getting hurt simply living your life is more than a little silly, especially if a little strength training would probably have prevented the injury.

One myth about strength training that stubbornly continues to maintain itself is that by lifting weights, you will become bulky because of the muscle gains.

Nothing could be further from the truth. This is great if you don’t want to lift because you fear getting bulky and infuriating for those who try everything to build large amounts of muscles mass.

When you see enormous bodybuilders on the covers of magazines, you can be pretty certain that one of three things is going on...

- Somebody’s been busy with an airbrush on the photo.

- The person pictured is extraordinarily genetically gifted for muscle growth. In other words, they’re freak. If you were in this category, you’d know it already.

- They’ve had some chemical assistance, i.e. they used performance enhancing drugs to help them grow.

There is no denying, as some do, that anybody who is that size and, in that shape, has worked hard. But it doesn’t follow that if you and I work that hard, we’ll end up at a shredded 250lbs.

Gaining muscle is notoriously hard. People who claim to have gained “10lbs of muscle in 12 weeks” are usually trying to sell you something and it’s something they can’t deliver.

Whilst it’s true that “mass moves mass”, the point at which strength relies on mass is a lot further along the performance curve than we’re talking about here. I’ve seen a 185lb man deadlift 600lbs. He didn’t have a lot of mass to move that mass!

Rest assured that you can get very strong without building a lot of extra muscle. Unless you want to build muscle, in which case it’s hard but can be done as long as you are patient and consistent with your diet and training (how to do that is another article entirely).

In the quest to better entertain their members and clients, gyms and trainers have invented some interesting takes on strength training, none of which are effective for strength training at all.

It can be argued that most have a place in the fitness world, but true strength development is not that place.

During my time working for British Cycling, whenever I was in meetings where coaches were asked to develop CPD workshops about strength training for cyclists, it wasn’t long before someone stridently presented the opinion that all movements trained should be imitations of the movements that would be performed on a bicycle.

This isn’t confined to cycling, I’ve seen it elsewhere. There are videos on Youtube that show elite athletes doing things in the gym that look remarkably like their sport, overseen by their S&C trainers who really should know better.

The problem here is that during the practice of most sports, similar movements are repeated often. Athletes become strong in those movement patterns and weaker in patterns that aren’t used in that sport.

Even their bodies start to take the shape that you’d expect from someone who does that sport; back to cycling, I’m sure most of us could spot habitual cyclists simply by observing their posture as they walk across the room.

The purpose of strength training is not to reinforce these patterns, but to train all the basic human movement patterns, thereby building a more robust human body.

What I refer to as strength cardio is one of the health club industry’s attempts - very successful may I add - at entertaining their clients with weight training set to music.

Bodypump is one of the original versions of this type of workout. Whilst very popular and sometimes quite effective in helping some people to lose weight, the high rep, low weight nature of these workouts is not ideal for building strength.

The loads simply can’t be heavy enough to elicit a true strength response. Also, the level of fatigue you’ll experience in an hour-long class means exercise technique is sure to be compromised at some point, thereby increasing injury risk and poor patterning.

Instead, it’s a form of conditioning workout with some added load. You’re not going to get strong doing strength cardio. For conditioning, you’d probably be better off going for a run, but if you enjoy it there’s no reason not to do it.

Circuit training differs from strength cardio in that it’s likely to be far more interval-like in nature, with shorter efforts and longer breaks.

This means that at each circuit station you could potentially move more weight, but this is still not likely to be all that heavy. The instructor will have planned the class (assuming they did plan it!) so that the average participant could complete the time at each station with good form and without risk of concentric failure.

Also, because circuits are usually planned to be “whole body” sessions, no movement is likely to be loaded enough to elicit a genuine strength response. Three circuits of about a minute per exercise with a minute to switch between exercises, using a weight that is nowhere near the limit for that minute won’t make you much stronger, if it makes you stronger at all.

Again, it’s more of a conditioning session than a strength session.

Boot camps are effectively outdoor circuit classes, but I’ve given them their own category because the purpose of most boot camp fitness sessions appears to be to get sweaty and sore.

They’re effectively entertainment for the masochistic among us.

"If all you want is to get sweaty and sore;

Go and sit in the sauna and get someone to hit you with a big stick!"

- Andrew Read

Circus tricks are the domain of most Instagram fitness influencers, but it’s not limited to them by any means. Much of the “functional fitness” movement falls into this camp too.

Doing handstands atop a stack of weight plates or squats on a swiss ball isn’t going to make you strong. It will impress your mates, and it will look great on Instagram.

Arguments about working from an unstable base are just silly. Nobody is going to squat anywhere near enough weight whilst standing on a Bosu ball to get even vaguely strong. And if they get it wrong, they could be in for some expensive surgery.

There is no reason not to learn how to do a solid freestanding handstand, planchet, front lever, human flag, or a host of other impressive feats of strength, but they’re gymnastic feats you add to the strength you’ve built, not the road to that strength.

The machines versus free weights debate has consumed many a Facebook thread and, prior to the internet, many a heated discussion. There are proponents on both sides and a balanced argument makes the case for both having their uses.

This is about tools and methods, not religion. If all you have access to is a free weights gym, you can get similar results to those you could get in a solely machine-equipped gym or with no gym at all.

Health clubs love machines because a room full of machines looks high tech, they’re fairly neat - they fit in one space and don’t move around - and they take very little expertise to use. Thus, they argue they’re safer to use.

They are most certainly a very good innovation if you’re a bodybuilder, doing most of your training to concentric failure. They’re designed so that you’re less likely to drop a large weight on your head when your Central Nervous System decides that it doesn’t want you lifting that weight anymore.

Failing on a chest press machine may make a lot of noise, but it’s a lot less catastrophic than dropping a heavy barbell on your neck if you fail at the bench press without a spotter!

The biggest problem that arises with machines is that it’s impossible to design a machine that adjusts to fit every person who will use it. So, they’re designed for an average sized person or often a slightly larger than average person.

By definition, pretty much nobody is average. This means that you could find yourself having to move the weight in a way that places your joins in a compromised position. It won’t take long before that machine that is so “safe” becomes the cause of your injury.

Also, machines don’t require you to learn the correct pattern for a movement, with the correct involvement of synergistic and stabilising muscles. In the real world, which is what we’re training for after all, these are usually the limiters, not the prime mover muscles.

Free weights, on the other hand, require that you learn how to perform a movement correctly, developing a path or groove within which you perform it. Your ability to move the weight correctly is limited by the ability of your synergists and stabilisers to do their job properly.

They do have the disadvantage that if you want to lift heavy weights, you need a competent spotter (someone who will be awake to when you’re about to fail to assist you not to drop the weight on your head) or some sort of safety device like a squat rack.

If you’re working out at peak time in a commercial gym, it can be difficult to find space in the free weights area and you might need to summon up a bit of courage to squeeze in amongst people who look like they really know what they’re doing (tip: many of them don’t) and who are lifting more than you could imagine. Generally speaking, these are some of the nicest, most welcoming people in the gym.

Of course, because you need so little equipment to have an effective free weights setup, you could just forego the gym membership and buy your own equipment to use at home.

An alternative to the gym or buying much equipment for home use that has become quite popular is calisthenics or body weight strength training.

As long as you can find somewhere to do pull ups or suspend some gymnastic rings, it’s easy to start and you can scale most exercises to suit the level you’re at.

What’s more, as you progress, there are harder versions of almost every exercise to keep you engaged for years and you can get impressively strong doing it. The key here, as with any strength training is patience.

Raw or Equipped - Belts, Straps and Wraps?

Visit any gym and you’ll see people lifting not very heavy weights whilst kitted out like powerlifters or strongman athletes. Knee wraps or sleeves, elbow sleeves, lifting belts and lifting straps; these are considered by many coaches as indispensable safety aids.

In reality, most of them are simply crutches in most situations. Remove them and you immediately expose glaring weaknesses in the lifter using them.

Your grip is part of the feedback mechanism about your ability to activate your core properly. If you can’t hold onto the weight you’re lifting, there’s a reason. In many cases, it’s an inability to properly pressurise your core musculature so that, among other things, you support your lumbar spine in a neutral position. Add lifting straps and yes, you will be able to lift more, but at what risk?

Your core musculature - Transversus Abdominus, pelvic floor and diaphragm - are designed to be able to provide all the pressure you need to support your lower back throughout your daily life, including when you lift heavy items. Using a belt correctly still requires this ability to pressurise, but used incorrectly, it provides support that in place of that inherent ability. Unless you wear a lifting belt all day, every day, would it not make more sense to teach the musculature to do an ever more effective job?

One can make a similar argument about knee and elbow sleeves and wraps.

These items have a place, but it’s in a strength sports context. They aren't safety aids, they're performance enhancement aids.

When you’re lifting to get strong for life or to enhance your sports performance elsewhere, it makes far more sense to progress slowly and build a strong, even bulletproof body.

When you set out on your strength training journey, there is more than one route you could follow. What follows are three broad categories of strength qualities. What’s great is that they all affect each other to some degree.

You can and should combine them to some extent. Extreme specialisation is a sports specific approach that serves no balanced human well at all.

This is exactly what it says it is: the ability to move as much weight as possible in one go.

In a sports context, powerlifters are the ultimate expression of maximum strength. Powerlifting competitions consist of just three exercises (Deadlift, Squat, Bench Press), in which the lifters aim to lift the maximum they can in each and to have the largest overall total from the best of each of their lifts.

It’s often thought that powerlifters don’t need to be all that fit, but as they need to recover between lifts, a good level of conditioning is helpful. The old caricature of the big fat powerlifter no longer holds true. In most cases, these guys are in awesome shape.

Whilst it’s not necessary to test your maximum lifts or always to be training close to that level, you need an element of maximum strength in your strength training programme.

I like to think of this as “headroom”. The higher your maximum strength, the more space you have below that in which to work.

When you’re training for maximum strength, there are some very popular approaches, including 5 x 5, singles, and 5/3/1 to name but three.

As you get older, a lot of heavy volume gets tricky to recover from and the risk to reward ratio shifts very much towards the risk side of the equation. With that in mind, I quite like a simple 3 sets of 5 reps with plenty of recovery time between. You won’t become a world champion powerlifter, but you’ll get plenty strong with less risk.

Hypertrophy is the building of muscle size and lean mass. I refer to lean mass as opposed to muscle mass, because in most cases people who have a lot of lean mass are not only carrying muscle mass. They also develop more bone mass, tendon size and strength and hold more water within and between muscle cells; all of this is lean mass.

Bodybuilders are the epitome of hypertrophy athletes. Building their mass takes a lot of intense lifting training and an intense focus on eating enough food, seemingly eating all the time to fuel muscle synthesis.

Just when you think they’re done with discipline, it gets harder as they then set about dieting off their body fat whilst maintaining their training at as high a level as possible, in order not to lose their precious mass gains. When they’re in stage shape, bodybuilders have usually shed as much water as possible, so that their lean mass is muscle, bone and connective tissue.

The good news is that any strength training you do will enhance your lean mass and you do not have to live the monastic existence of a serious bodybuilder to gain muscle.

Having said that, contrary to what many of the body recomposition experts say, the main purpose of strength training is not the addition of size to your frame, it’s an increase in how strong you are relative to your body mass.

We’re not all built to be giants, we’re not all built to have that perfect bodybuilder physique (if you think that’s perfect that is) but we are all built to be a lot stronger than most of us are.

Because hypertrophy training requires building significant fatigue in your muscles, the most common approach is sets (3 or 4) of between 8 and 12 reps with only as much rest as you need to recover (usually 30-60 seconds). I like to add a time under tension component, aiming to be moving the weight for between 45 and 60 seconds.

Strength endurance is what I like to think of as work capacity; the ability to bring your strength to bear in a situation and to keep doing so until the job is done.

Think about it this way: Who is more use in a crisis? The person who can lift something heavy once or twice and then needs a long rest? Or the person who can lift less weight, but who can keep lifting that lesser weight all day?

Clearly, this will differ based on the task at hand, but it’s usually the person with better strength endurance who proves to be more useful.

As much as CrossFit gets a bad rap, their athletes demonstrate remarkable strength endurance across a multitude of tasks.

To a degree, you also see this in Strongman events; while the loads are heavy and the events are time-limited to around 75-seconds, you’ll observe that the best competitors fade the least in the later seconds of their events. This is strength endurance in a very heavy setting.

Along with a level of maximum strength, strength endurance is the quality we most need if we’re to be balanced physical humans. The strength standards I outlined in my article about athletic readiness should be exactly that balance.

The best way to train strength endurance is using some form of interval training, where you aim for fairly long sets and shorts rests. These will often include some level of cardiovascular element too. The Murph workout is a good challenge of strength endurance, as is the 5-minute kettlebell snatch test.

When people talk about strength training, they’ll often talk about compound exercises, assistance lifts, isolation exercises and to a lesser degree, unilateral exercises. You should be using them all. Here’s a quick description of each.

Compound lifts are the big, whole body movements that should be the cornerstone of your strength training programme. They involve the greatest amount of muscle mass and the maximum coordination of prime mover muscles, synergistic muscles and stabilisation muscles.

Generally speaking, compound lifts are loaded versions of the basic human movement patterns. Examples are...

- Hinge - Deadlift

- Squat - Low Bar Back Squat

- Push - Bench Press

- Pull - Pull Up

While it can be tempting to think of these as the only compound movements, nothing could be further from the truth. Lunges, kettlebell swings, pull ups, press ups and a host of other exercises qualify as compound lifts. The key determinant is that you’re performing a full pattern under load, whilst having to control and coordinate multiple joints and a lot of muscle mass.

Isolation exercises are most commonly employed by bodybuilders and those folks who have an obsession with aesthetics, e.g. people who are obsessed with having bigger biceps.

The idea is to remove the core stabilisation demand and the need for synergistic/stabiliser muscles as much as possible, so that you can maximally stress one particular muscle or muscle group, forcing it to grow.

These are not the ideal place to start with your strength training, but may have utility as you progress your lifting.

Assistance lifts aim to address specific weaknesses in a compound exercise. These can be versions of compound lifts or (semi) isolation exercises. This is probably best illustrated with two examples.

Imagine you’re struggling to get the weight to break the ground on your deadlift, but your lockout is strong. It makes no sense to keep trying to improve by just doing more deadlifts because progress will be slow.

Instead, you need to work on your strength in that weak position. There are a few exercises you could do, including stiff leg deadlifts using a 1” deficit (you stand on a 1” block) or paused deadlifts (using a lighter weight, you pause after lifting the weight an inch or so and then complete the lift). These are modifications of compound lifts.

In the other example, you might find that you struggle to complete a set if pull ups because your biceps tire too quickly. The simple solution here is to spend some time doing chin ups at the end of your workouts (semi-isolation) or if you’re really struggling, start with simple dumbbell bicep curls and progress from there.

Working on assistance lifts can be a very effective way to break a strength plateau.

One area that many, if not most lifters tend to ignore is unilateral exercises. As far as I can ascertain, this is usually for one of two main reasons...

- You must use far less weight. This can be hard on the ego.

- Unilateral exercises are challenging and can often be painful.

Whilst the big exercises (squats, deadlifts, bench press etc.) and their variations will recruit the most muscle mass, life is not generally lived in a stable environment on two feet or using two arms.

This is where unilateral lifts come in.

Training on one leg or using one arm promotes coordination and balance, thus building your force production capacity for the real world.

Much like anywhere else in the 21st century world, the strength training world is filled with acronyms and jargon. Here are a few of the more common ones you might encounter.

Also simply referred to as “failure”, this is when you can no longer perform a repetition. There are two versions of this.

One is catastrophic failure, where you’ve pushed so deep, your muscles simply fail and you drop the weight, hopefully not on yourself. This is the result of trying to get “one extra rep” at any cost, no matter how poor your technique or the injury risk on that rep. It's these that appear on Youtube as "Gym Fails".

The other, safer method could be referred to as “technique failure”, that point at which you can no longer perform a perfect repetition. As soon as you need to start performing a “funky dance” to finish a rep, you are done.

Failure is important for those who are trying to build muscle mass but can be detrimental if you’re trying to build the ability to lift the most weight possible. The “funky dance” takes you out of your ideal movement groove and has you trying to develop force in a less than ideal manner. For strength development, it’s usually better to leave a rep or two in the tank.

Very popular in the CrossFit world, AMRAP stands for "As Many Reps As Possible". This is usually within a set time period but can simply be as much as you can do before you get to concentric (or technique) failure.

Another term that was popularised by CrossFit is EMOTM, which stands for "Every Minute On The Minute". It’s a way of manipulating the density of your workout by using turnaround times rather than set rest intervals.

“Every thirty seconds on the thirty seconds” or “Every 2 minutes on the 2 minutes” don’t make for as snappy an acronym, but the principle is the same.

Rest intervals are exactly what they say on the tin. Whenever you finish a set, you grab a look at the clock and rest for the appropriate amount of time.

Your rest interval includes the time it takes to set up for the next set, meaning you need to be ready to start the next set as soon as the rest interval expires. This is a mistake a lot of people make: allowing their rest intervals to drift.

The reps in reserve concept is a little more complex than my simple description here, but this is all you really need to know.

Rather than training to failure, you always aim to finish any set a few reps shy of failure. With experience, you learn how many reps you should achieve in a set and terminate the set two or three reps short of that number. With a little more experience, you develop a sense of how much you have left in the tank and can be pretty accurate.

Pick a number (usually 2 or 3) and always stop when you get there.

One benefit of this approach with strength training is that you run far less risk of catastrophic injury than you do with a method that requires pushing sets to failure.

Another benefit is that you’re always practising a strong and accurate groove for your lifts, whereas failed reps often follow a very different path as you try your best to complete the lift, in many cases trying not to drop it on your head.

Almost any lifter who believes they’re advanced is in fact still a beginner (I count myself in that group, even though I have some lifts where the load I’m moving would be considered advanced).

The basics work and will always work. Many of the fancier techniques are only particularly effective when used by lifters who are using performance enhancing substances. A natural lifter might get an effect, but it’s unlikely to be a large effect.

They’re also primarily used by bodybuilders as a way to drive more muscle growth.

With that in mind, the advanced tactics that follow aren’t necessarily applicable. I’ve included them for completeness because they’ll almost certainly pop up from time to time.

Forced reps are performed with the aid of a spotter after you’ve reached concentric failure. Your spotter performs the concentric movement for you, and you lower the weight (the eccentric phase) as under control as you can.

Ideally, you want to do as many reps this way as you can until you reach eccentric failure - i.e. you can’t even lower the weight under control anymore.

The theory is that because you can lower about 40% more weight than you can lift, doing forced negatives fatigues the muscle even more, promoting more muscle growth.

Like forced negatives, forced reps involve your spotter. Except that this time, they provide just enough assistance to allow you to complete a few extra reps.

Some would say these are not real reps because your spotter is helping you. However, if it’s muscle mass you’re after, how many reps you complete is less important than how much micro-damage you can do in your session, so that you have something to recover from.

Drop sets are a little like forced reps, except that your spotter doesn’t provide assistance to complete the reps.

Instead, you complete a set to failure, strip a small amount of weight off the bar (or use a lighter dumbell) and immediately do the next set to failure. Strip a little more weight and do it again.

Keep stripping weight from the bar and lifting to failure until you have trouble lifting a broomstick.

Why? Same as the techniques above; more micro-damage = more muscle growth.

In blood flow restriction training, you reduce the amount of blood that can get into the muscles, meaning that you can train that movement to failure with a far smaller load.

Generally speaking, you only want to restrict about 25% of the blood flow, not cut it off completely. You also want to stop if the limb which you’re restricting goes numb or starts to tingle.

The weights you use should be significantly lower than you’d normally lift, and rep ranges much higher. Some experts recommend sets of as many as 30 reps with blood flow restriction.

Once again, this is a technique usually employed as a way to drive greater muscle growth, but I’ve found it really useful as a way to work around joint injuries (like “old man elbows”, that can result from doing lots of pull ups). Because you can tire the muscle out with far less weight, the stress on the joint is reduced, allowing you to continue with at least some training while the joint heals.

Strength matters.

Some would argue that strength is the pre-eminent quality for human beings. It’s certainly true that having a strong and capable body is a strong marker for living a long, high quality life.

With that in mind, I repeat: Everybody should do strength training in one form or another.

You most certainly don’t need to take part in strength sports to be strong. I know I don’t.

You don’t have to be built like Arnold or any of his Mr Universe successors. Again, I know I’m not that either.

You do however need to be strong and capable if you’re to be independent for as long as possible or better...