Specific workout planning is important once you've planned your overall programme. Part 3 of the "How to Plan Your Own Training" series.

Introduction

Once you’ve planned your broad training year, month, or week, you come to specific workout planning; what you’re going to do in each specific session.

It would be easy to simply decide on a workout duration for each session and then to do whatever you feel like for that time. However, this is a waste of all the time you spent figuring out the demands of your event (what you need to do to be successful at it).

We’re now going to look at how you turn those event demands into specific workouts that make you better at exactly those things.

This guide is meant to be a basic introduction to specific workout planning. Of course, there are a bunch of more advanced techniques that you can add to your workouts to make them even more “cutting edge”.

The truth is that these are mostly advanced techniques that are designed for use in one of three situations:

1. Advanced athletes, who have tapped out all the gains they should expect to make as a beginner/intermediate and who need more stimulus in order to keep improving. Most people who like to think of themselves as advanced athletes are in fact just beginners.

2. Athletes who use performance enhancing drugs and are thus able to work harder and recover faster than those who don’t.

3. Personal trainers who need to entertain their clients, because novel, advanced techniques look so much more impressive in a workout routine than simple, consistent hard work.

You certainly may wish to include more advanced techniques in your workouts, but don’t fool yourself that they’re the “magic sauce”; from over 20 years as a coach and a lifetime as an athlete, I’m confident that there is no such thing.

Get the basics right, do the work consistently and most of the desired results follow along quite predictably.

Consistency is the only hack that works every single time.

- Will Newton

Elements of Specific Workout Planning

Here are the main elements that you might wish to include in your workouts and some ways that you could include them for best effect.

Warm Up

Many people consider warmups as an afterthought and reduce them to simply a few swings of the arms or a thoughtless jog on a treadmill. There are times when a structured warmup is probably unnecessary, but there are others where it might dramatically improve the outcome of the workout itself.

Why warm up?

Warmups achieve two key things for you as an athlete (and one for a face-to-face coach).

- They help you switch on physically, increasing heart rate, increasing tissue temperature etc.

- They help you switch on mentally, getting your mind away from the half-finished project at the office and onto the task at hand.

- If you’re working face to face with a coach, your warmup can also serve as a way for them to assess your current physical state, your readiness for the workout and your technical proficiency.

Who needs to warm up?

Warmups are like so many things in the physical training world in that they have proponents and opponents. It’s by no means clear that a warmup is always needed. So, let’s discuss some situations in which they’re probably necessary.

- Older athletes - The older you get, the longer the warmup you’re likely to need. It takes more time for an older athlete to increase tissue pliability, joint lubrication, blood flow to the tissues and a safe increase in heart rate. Children seldom need to warm up; most of us have seen kids go from zero to running around in a heartbeat.

- Intense training sessions like intervals - The more intensity you plan to include in the session, the more likely you are to need a warmup, for both safety and the effectiveness of the overall session.

- Competition - Developing a warmup routine that you use in key sessions and repeat before competition is good practice. Not warming up properly before competition is a great way to suffer severe oxygen debt in the first few minutes. I think of this as a panic response that is likely to make you dig deeper into your glycogen stores than you’d want to do early in your event.

What should a good warmup include?

A good warmup should be…

Specific - It should prepare you for what you’re about to do. In other words, the warmup you use for swimming shouldn’t be the same as for running or lifting. If you’re doing a cycling session, warm up on the bike.

This specificity should also extend to any technical components you wish to work on in your session. If you’re going to practise moving mounts and dismounts on a bicycle, do you have the mobility to do so? Including some element of that in your warmup makes sense.

Whilst they may include some common elements, weight training warmups should always include some elements of activation for the movement groups you’re planning to train. An example would be the use of Clamshells and/or Fire Hydrants before deadlifting.

<image>

Progressive - It should increase in physical intensity (easy to hard) and complexity (technically simple to more complex) across the workout.

In swimming, we usually start with relaxed, easy full-stroke swimming before introducing any drills or short sprints. It’s a rare session that goes hard from the start, and one that would have to have a very specific purpose, like race preparation.

Dynamic - It should emphasise moving. This is less of an issue for people planning their own training than for coaches working with groups, where they’re likely to do a lot of talking and not so much activity.

Fitness (Physiological) Component

This is the piece that most athletes think of as the most important part when doing specific workout planning and is often the only thing they consider.

As important as it is - after all this is about improving physical performance - you’ll see further on in the article that there are other components you could address alongside the fitness element. These can often be as important to your overall success as simply your maximum lifts or your functional threshold power/pace.

When addressing the fitness component, it’s important to know what you’re trying to achieve and choose the right tool for the job.

I discussed the components of fitness and their definitions in part one of How to Plan Your Own Training; this time we’re going to look at ways to train each one.

While I discuss these as discrete items below, keep in mind that they are interlinked, so that training one component can positively or negatively affect several others.

Cardiovascular or Respiratory Endurance (includes all intensities that require oxygen)

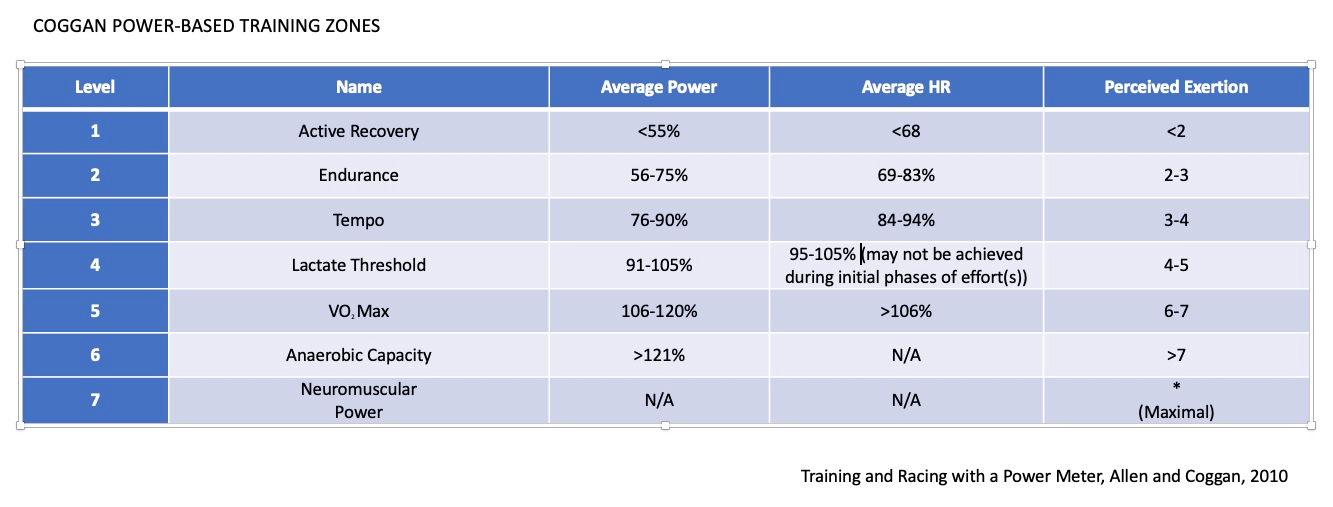

Because cardiovascular endurance is such a broad category, training it effectively requires that we break it down into a few parts. These are usually addressed by using specific heart rate zones, power zones or perceived exertion (RPE).

There are a bunch of different versions, which essentially say the same thing in different ways. Because he combines power, heart rate and RPE, I use those designed by Dr Andrew Coggan.

These are based on what is referred to as functional threshold power or heart rate, as opposed to maximum heart rate that is more often used. This has always made more sense to me because testing functional threshold is far more accessible (and safe) for a wider variety of people.

Long Endurance

Developing long endurance fitness simply requires that you spend a long time training at a relatively low intensity. That’s the key point here: relatively low intensity.

It’s time spent in zones 1 and 2 as set out above, or training at or below MAF as set out in this article.

The mistake most people make when training for long endurance is that they train at far too high an intensity, spending most of their time in the “grey zone” that is described by Coggan as zone 3 - tempo.

At this intensity, you get little extra in terms of fitness, but the cost in fatigue (and thus required recovery time) is far higher.

It’s usually not necessary to warm up for these sessions because the intensity is low enough that you can build into it across the first few minutes of the workout.

Lactate Threshold

These are sessions just below, at, or just above your functional threshold.

Functional Threshold is the level of output that someone with a bit of training can sustain for about an hour, but it’s usually tested over a 20-minute effort and adjusted down by about 5% for power. For heart rate, it’s very close to what you can sustain for 20 minutes.

Specific workout planning to improve your ability at threshold is going to involve interval training. Simply doing a one-hour effort every week will result in you being very tired and compromised for the next week’s training.

The traditional cyclist version of threshold intervals is 2 x 20-minute efforts. This is incredibly hard and most of us won’t do this more than a few times. A far better approach would be something like 3 x 8 minutes with 5-minute recovery between efforts.

For runners, slightly longer intervals are probably better, for swimmers, quite a bit shorter. To a degree, this is a case of working out what works for you.

You can play with the durations of the intervals, reduce the recovery periods a little etc.

The key point here is that you’re working very close to the level at which the burning sensation in muscles and lungs is urging you to stop. You’re getting used to the sensation and teaching your body to use the accumulated lactate more efficiently for fuel.

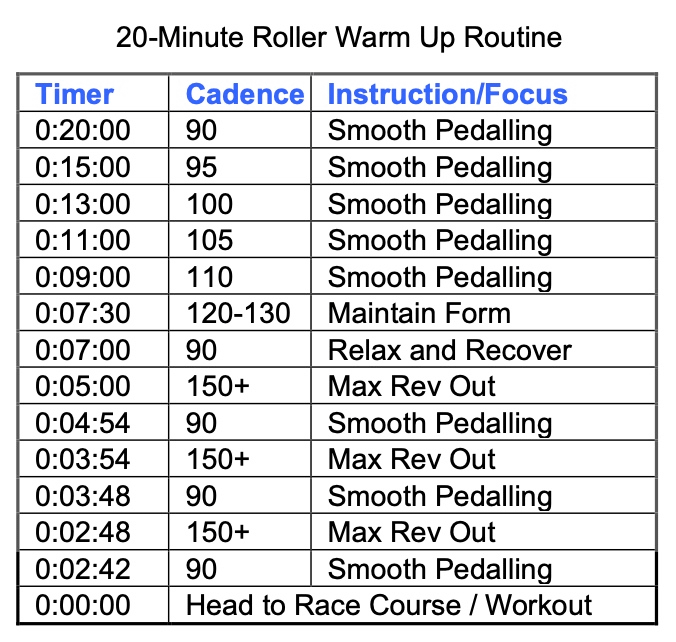

A good warmup is essential or you’re likely to “blow-up” during the first interval. This is my cycling warmup for any interval session. It’s perfectly possible to develop something similar for running, swimming or any other sport.

VO2 MAX

Vo2 Max refers to the maximum amount of oxygen your body can take up and use. It’s the level of effort you can maintain for about 5 minutes. There’s a training effect, so for a well-trained athlete this will be longer, whilst for someone untrained, it will be significantly shorter.

The best way to improve your VO2 Max is to use something like Billat Intervals. The linked study provides recommendations for runners, but they’re as valid for any other sport that requires high VO2 Max.

In order to be able to do these, you need to know your power, pace or heart rate at VO2 Max, which you can establish by running, cycling, swimming or rowing (other sports are available) as hard as you can for 5 minutes. The average pace, power or heart rate you achieved should approximate your VO2 Max.

For the intervals, warm up thoroughly and then perform as many sets of 30-seconds at Vo2 Max pace, power or heart rate followed by an easy 30-seconds to recover. Stop when you can no longer achieve VO2 Max. Veronique Billat developed other versions, but these are the simplest and least intimidating.

This type of training hurts, but it’s effective. It’s important to note that most people will plateau after 4-6 sessions and there is little benefit to be gained by doing more. Give it a few weeks break and return for another few sessions.

Supra-Maximal

This is mostly anaerobic work of very short duration, like sprints.

For most of us, if you’re “sprinting” for more than about 8-seconds, you’re not sprinting.

I’ve included it here because it’s part of the endurance arsenal, although it fits just as well into the strength and power components of fitness too.

A good warmup is vital for these, especially as we get older. Sprinting can be very hard on the body and doing so from cold is just begging for injury.

In your specific workout planning, keep in mind that sprinting is hard on the central nervous system (CNS), requiring quite a lot of recovery, even though you may not feel physically tired. People who advocate sprinting 3 times per week really don’t understand this. If they don’t get injured, it’s because they’re lucky!

Between 4 and 6 all-out sprints is all that most people can manage. Once you fall more than about 20% short of what you achieved in the first effort, it’s time to stop.

Rest breaks need to be long - often 10-minutes or more - if you’re going to be able to give 100% on every sprint.

Stamina

Stamina could also be called work capacity and it’s important in sport and life because that ability to keep going when things get tough is what separates the best from the rest.

Specific workout planning for stamina involves balancing a number of factors.

- Load (weight lifted, power output, pace) - Too low a load means you need a long workout and might not achieve the intensity you need to make the adaptations you’re after. Too high a load means you won’t finish the workout.

- Intensity (pacing) - Too high an intensity means you won’t finish, too low means you’ll need a long workout which might not provide enough stress to cause stamina adaptations.

- Rest Intervals - These matter because you want to get enough rest to keep going, but not so much that you recover fully. Years ago, I trained for a 10km race by running each km at my target pace (faster than I could run 10k) and taking just enough rest to be able to do the next km at that pace. When I got it right, each interval was bang on target and I was still running a fast 10k, even when the rest intervals were included.

Good examples of work capacity (stamina) workouts can be found all over the Crossfit community. Think what you like about Crossfit, but they’ve got stamina nailed.

A simple example of a session that addresses stamina, using turnaround times is this one:

Set a timer to beep every 30 seconds…

Perform 10 left-handed kettlebell swings, rest until the beep.

Perform 10 right-handed kettlebell swings, rest until the beep.

Repeat for 10 minutes.

After a few sessions, either reduce the turnaround time or increase the weight of the kettlebell you’re using.

Strength

The best expression of strength is the one repetition maximum lift for a particular exercise. Eddie Hall’s 500kg Deadlift is one such example.

But it doesn’t have to be one single lift that causes you to pass out, lose your vision, give you the symptoms of concussion etc. In fact, that’s a really poor idea.

Especially as we get older, going for maximum lifts becomes harder on the body and CNS, forcing us to look for the approach that gives us the biggest return on our effort investment.

Specific workout planning for strength should ensure that you’re lifting a heavy enough load that you have to recruit a lot of muscle fibre in that movement pattern. Something you can lift for between 3 and 6 repetitions is about right.

If you’re lifting something so light that you can do 15 repetitions without breaking a sweat and still have 5 left in the tank, that’s not strength training.

Rest intervals need to be long in order to allow those fatigued motor units to recover enough that they can repeat the lift; 3-5 minutes or more, depending on the load.

There are a lot of suggested rep schemes and none of them are wrong.

Personally, I like 3 sets of between 4 and 6 lifts. It’s heavy enough to cause the adaptations I want, without being so heavy or so much volume that it compromises everything else.

Look for what are referred to as compound movements, those that use the most muscle across the body to perform them and make those the focus of your lifting programme.

One compound movement for each of the basic human movement patterns is the ideal, with what are called accessory movements that address any specific weaknesses you may have in those movements.

Important: Before doing heavy lifting, get some instruction from someone who knows those lifts really well and learn the technique. Most of the time, the spotty kid looking after the leisure centre gym is not that expert!

Flexibility (I prefer the term "Mobility")

If you lack mobility, you’ll be compromised in many of the other components.

- Unable to get into position to generate maximum strength.

- Unable to stride out when running hard, meaning the extra effort doesn’t equal more speed; or you’re fighting yourself and get tired before you should.

- Lack the agility to respond reflexively without hurting yourself.

Mobility sessions are usually standalone sessions and are often missed in specific workout planning because of time constraints. However, including them can make the difference between losing time in training and maintaining that all-important consistency.

When planning mobility training, focus on tissue quality first, using foam rollers (like this example), lacrosse balls and other tools to mimic what a massage therapist might do.

Follow that with some work on tissue length, which is essentially stretching

Finally, remember that mobility is flexibility under control. This means you need to work on having control of the terminal positions of your flexibility. Only where you have that, will your CNS allow you to access all of that flexibility.

There is no definite list of things that you will need to address in your mobility workouts, but the most common areas that people have trouble with are…

- Hips and hip girdle (glutes, hamstrings, hip flexors, quadratus lumborum)

- Ankles (tight calves, weak anterior tibialis)

- Thoracic spine

- Shoulders (internal and external rotation)

Find where your issues are and create a plan to address those areas. These sessions need be no more than 15 minutes (lots of folks do them with the kids or in front of the TV).

Power

The simplest expression of power, one that most of us have seen at one time or another, is that of the Olympic weightlifter.

Because it’s the ability to move a load (could be yourself) over a distance in the shortest possible period of time, Olympic lifting is a very good way to train it.

It’s also a potentially risky way to train it because it’s technically demanding.

You can achieve a similar effect without the loading by programming jumps onto a box, throwing medicine balls and sprinting into your specific workout planning.

Much like with your strength training, look at the human movements and think about how you could perform them fast, with body weight (for jumping) or a small external load like a medicine ball (for throwing).

Important: If you do want to try Olympic lifting, get some instruction from someone who knows those lifts really well and learn the technique. The leisure centre gym instructor is very unlikely to have this knowledge.

Speed

Speed is about how fast you move.

The restriction with speed is most often a CNS one. People who don’t move their limbs fast (cyclists who pedal slowly, runners with long loping strides) often lack the neural patterning to do so.

The solution is to use interval training, where the focus is not on physical effort (like in VO2 Max training for example), but on short bursts of faster movement.

Cadence training for cyclists is one such example. The session might only include a few 20-30 second intervals where you pedal at 120RPM, but those periods of high turnover slowly teach your CNS the patterns you need to be able to routinely pedal at that speed.

Another example is the kettlebell snatch test, which is performed at SFG and RKC training events. It consists of 100 snatches to be completed in 5 minutes with your snatch weight kettlebell (usually 24kg for men and 16kg for women).

Most people train to be able to perform the snatch movement with required weight but think little of the speed component. Learning to swing the bell faster takes more advantage of elastic rebound from your hamstrings.

Training a fast tempo with a lighter kettlebell (e.g. 16kg/8kg) teaches your nervous system to move this fast. The result is a far easier snatch test experience - although it’s never easy!

Coordination, Agility, Balance and Accuracy

I’ve lumped these into one category for the purposes of this article because there is some significant overlap between how you incorporate them into your specific workout planning.

Much of coordination, agility, balance, and accuracy are also related to the technique aspect of planning your workouts.

They’re best included using drills, where you isolate a part of what you’re doing and then reintegrate it into the full movement.

One example is swimming drills, which are best performed in sets of something along the lines of 25m drill into 25m full stroke swimming. The drill emphasises what you wish to work on and the full stroke swimming integrates that part of the stroke back into real swimming.

Some swimmers simply do drills all the time and get very good at drills, they don’t get better at actually swimming.

Something similar works in the gym, where you might learn the movement required for a barbell snatch using a broomstick or PVC pipe. The lack of load allows you to groove the movement. For this to be effective, however, you do need to load the movement at some point.

You might also practise parts of the snatch movement in isolation using drills that give you a feel for that isolated piece (e.g. the catch), but at some point it needs to be integrated into the whole movement. There are no medals for the prettiest catch phase!

Drills in the running world use hurdles, foot-speed ladders, and a host of other tools. In the cycling world, rollers and turbo trainers allow the rider to focus on parts of the pedal stroke without worrying about traffic (I prefer rollers because of the balance component).

Regardless of what drills you’re doing, remember: Isolate

Reflexes or Reaction Time

Even if your sport doesn’t require reflex reactions, life does and it’s worth training.

Specific workout planning for reflexes and reaction time doesn’t have to be complex. In fact, my favourites are playing badminton with my son or throwing a reaction ball against the wall and catching it on the very random rebound, a version of which I spent hours doing as a 13-year-old cricket player.

Technique Component

Technique is an important part of any sport and can be addressed as part of a physical fitness focused workout, or you could address it in a standalone session.

Remember the drills discussed above when we talked about coordination, agility, balance, and accuracy.

The important general rule here is that technique should be addressed early in a session before you become too tired. Fatigue tends to degrade technique, especially where you’re trying to learn new ways to move. That degradation will result in the grooving of poor technique; not what you’re after.

There is a counterpoint to this and it’s in the case where your event will require you to maintain technique under pressure or in conditions of significant fatigue. In cases like this, it can occasionally be useful to reproduce the expected pressure or fatigue and focus on excellent technique under those conditions. I need to stress that this should be occasional, not every week or every workout.

Have another look at your event demands. What technique elements do you need to be successful?

Tactical Component

Tactics vary dramatically across sports and even different events within the same sport.

Including a tactical component into your specific workout planning will give you the opportunity to experience scenarios in training that you might encounter in competition.

This could be as simple as different pacing strategies for a distance runner or jumps in weights for a powerlifter, to playing out different scenarios in a group of cyclists.

Mental Component

The mental component can take a number of forms, three of which I address here.

1. Developing strategies for dealing with fatigue. Endurance athletes often have to deal with extreme levels of fatigue. This has a huge emotional component, something which can dramatically affect performance when unexpected.

Considering possible solutions and making those decisions beforehand takes out the need to make decisions during an event in an emotional state - something we all know is a very bad idea.

These strategies can be practised as part of occasional heavy fatigue workouts as mentioned in the technique component section above.

2. Developing strategies for dealing with pressure. Similar to number 1, planning specific workouts where you have to deal with the kind of pressure you might encounter in competition can help you to develop strategies to deal with that pressure.

3. Elite athletes have used visualisation as part of their armoury for many years. This can take the form of pre-workout or pre-event visualisation, or you can include visualisation during your workouts.

“The mind always fails first, not the body. The secret is to make your mind work for you, not against you.”

- Arnold Schwarzenegger

Intra-Workout Recovery Breaks

Especially when lifting or performing interval workouts, the work portion of the session can be dramatically affected by the rest portion.

Depending on the goal of your workout or your level of fitness, you might need longer or shorter rest intervals.

Examples:

- Maximum strength sessions require fairly long intra-workout recovery breaks because you want to have recovered fully between sets (3-5 minutes or more).

- Hypertrophy sessions need intra-workout recovery breaks long enough to recover partially, so that you can still achieve a high workload, but not so high that the session goes on forever (1-3 minutes).

- Work capacity sessions require just enough recovery to allow you to continue the session, but recovery is only partial. Part of the goal here is to decrease your rest to work ratio (start with a 1:1 work to rest ratio and progress to 3:1 or better).

Most core workouts that endurance athletes complete are work capacity sessions, because endurance sport is essentially about stamina.

If you train with others, remember that your recovery requirement might be difficult to your training partner’s. You can assess whether you’ve had enough recovery by monitoring your breathing, heart rate or just your sense of how well you’ve recovered from the last effort.

Cool Down

The need for a cool down follows similar rules to warmups, especially with regard to intense sessions.

The benefits of cooling down gradually include better venous return of blood to the heart, allowing the body to pump it out to the liver and kidneys to deal with waste products from exertion. This can help to reduce post-exercise soreness.

Another way to reduce stiff and sore muscles is to include some static stretching for key muscles that were most involved in your workout.

It’s even better if you add some mobility work for areas that might become immobile due to positions adopted during your sport. The obvious example here is the mid-back area (thoracic spine) for cyclists; this can become very immobile, especially with extreme aero positions adopted for long periods.

One of the simplest but most effective things you can do for a cooldown is to go for a 10-minute brisk walk. Focus on good posture, relaxed breathing, and awareness of any sore spots. Remarkably simple, works really well.

Important Concepts

There are a few important concepts to have in the back of your mind when it comes to specific workout planning. In order to avoid them getting lost, I’ve decided to put them in a separate section.

Maximum Recoverable Volume (or Stress)

Maximum recoverable volume (MRV) is something that gets discussed in the strength training world, but it’s no less applicable to any other training.

Strength guys define it as the theoretical point where the total number of sets performed by a muscle per week accumulates so much fatigue that your performance and results begin to suffer.

Across all training endeavours, there is a level of stress that is just right and promotes improvement, as well as a level of stress that is too high and causes us to break down. This operates on an individual workout-to-workout level as well as across longer periods.

I’ve mentioned the Dan John “Bus Bench, Park Bench” principle before. MRV is exactly that on a workout-to-workout level.

Bus bench workouts are those you perform every day. They should be long enough, hard enough, and dense enough to promote an improvement in performance, but no more. You should recovery from them soon enough to perform at the top of your game in the next workout.

Park bench workouts are those you do occasionally. You do them because you can, not necessarily because you should. There is a distinct possibility a park bench workout will hurt you. It will take longer to recover from than is ideal. Competitions fall into this category.

Doing park bench workouts all the time is a great way to break yourself and see your performance go backwards. Doing appropriate specific workout planning means you will avoid wasting your efforts on irrecoverable fatigue.

Reps in Reserve versus Failure

This is another strength concept that carries over to any other interval training.

When training for hypertrophy, lifters are looking for concentric failure and beyond, to cause as much muscle micro trauma as possible.

For strength training and across any interval training, failure is to be avoided as much as possible. That means that you should always stop one or two reps short of the point where it all falls apart.

By keeping a little in reserve, you are teaching your nervous system how to succeed. You’re also teaching it that there is nothing to fear. When you go to failure, you teach your CNS that there is a threat; the result is that it holds a little back. It’s better that you hold it back and don’t provide the threat.

Summary

Specific workout planning can appear extremely complex.

It can be, but this is usually the case with advanced athletes and as much as many people wish to believe they’re advanced, that athlete is rare.

With a little thought and some reference to the demands of your event, it doesn’t have to be excessively complicated.

Instead of going down the physiology textbook route, in which you try to define everything with numbers, ask yourself one simple question…

What do I need to be able to do to be successful?

Once you know that, write a plan with specific workouts that prepare you to do those things and do them consistently.